Low Earth orbit is today saturated with spacecraft and space debris of all kinds. In addition to having to find a place to evolve in this orbit, the machines are also subject to the threat of impact with debris; phenomena that are less and less rare in space. And during these collisions, the smallest pieces of debris can do significant damage. How can these millimetric objects have such an impact?

In 2016, European Space Agency astronaut Tim Peake shared a photo of a millimeter impact carved into a window of the International Space Station (ISS). The guilty ? A small piece of space junk. The piece of debris, possibly a flake of paint or a fragment of metal from a satellite, was only a few thousandths of a millimeter in diameter — not much larger than an E bacterium. coli .

But how can something so small cause such great damage? As Vishnu Reddy, an astronomer at the University of Arizona explains, it all comes down to speed. Objects at the altitude of the ISS and most other satellites — about 400 kilometers above Earth — orbit our planet once every 90 minutes, according to the European Space Agency. That's over 25,200 km/h, 10 times the speed of an average (gun) bullet fired on Earth, according to NASA flight instructor and controller Robert Frost.

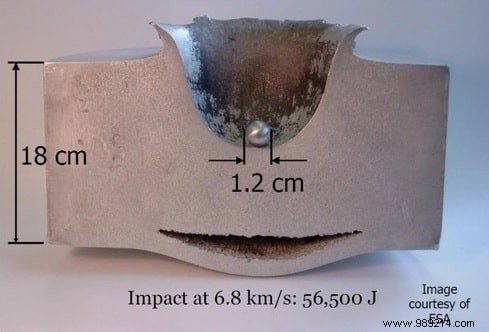

The energy of an impact is not only related to the size of an object; speed is just as important. This is why a very small caliber bullet can cause so much damage; moving at a high enough speed, any object can be dangerous. Speed is additive. So if two objects move closer to each other when they collide, it increases the energy of their impact. It's like an accident on a highway. Two fast cars moving in the same direction can touch and jostle each other. But if a vehicle — even a light one, like a motorcycle — hits a car while accelerating in the opposite direction, it could be disastrous for both drivers.

In space, satellites, spacecraft and debris orbit in many different trajectories; while one object might orbit horizontally around the equator, another might loop vertically around the poles. Some objects even move “in retrograde,” meaning they spin against Earth’s orbit. As more and more debris clutters space, low Earth orbit (in which the ISS operates) turns into a crowded freeway during rush hour.

Astronauts aboard the ISS were lucky that a bigger piece of debris didn't hit their window. A microbe-sized fragment may leave only a bump, but a pea-sized fragment can disable critical flight systems, according to the European Space Agency. A piece of debris the size of a ping-pong ball? That would be catastrophic, according to Reddy. At this size, space debris could cause rapid depressurization of the space station, threatening astronaut oxygenation.

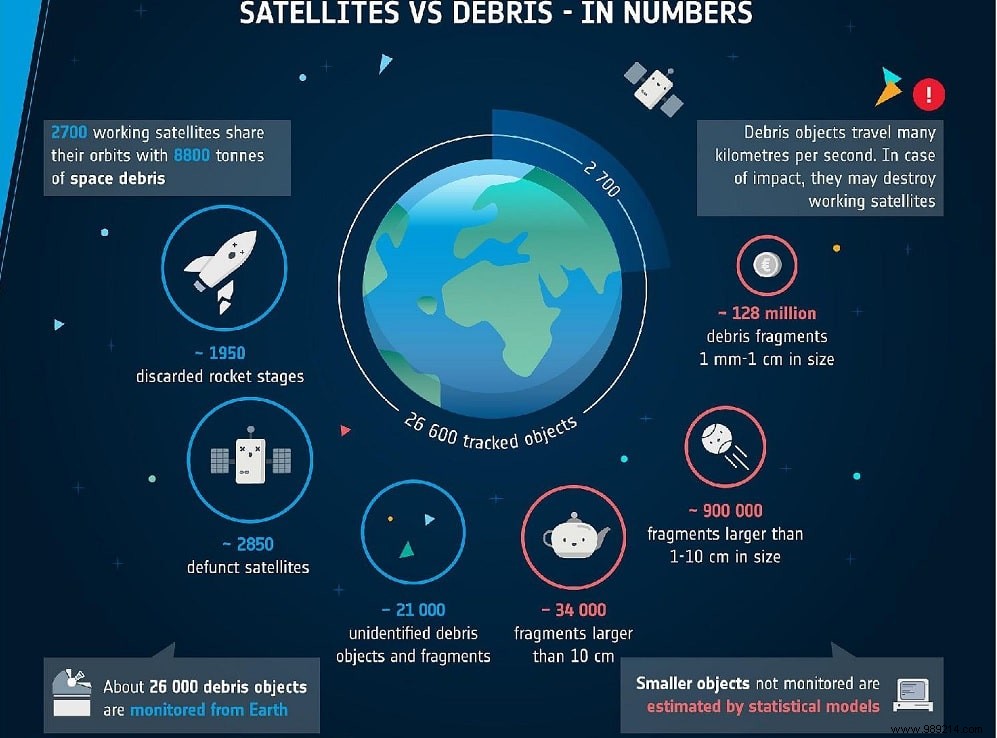

Space debris is a growing problem. Earth's orbit contains at least 128 million pieces of debris, and 34,000 of them are larger than about 10 centimeters, according to the Natural History Museum from London; and these are only the fragments large enough to be detected. These smaller pieces form when satellites are naturally exposed to extreme ultraviolet radiation, when larger space junk collides, or when satellites are intentionally destroyed.

Larger pieces include 3,000 derelict satellites, as well as other pieces ejected by spacecraft during launches. By tracking space debris, scientists can tell agencies and companies when to maneuver a spacecraft out of the path of an accelerating piece of debris.

The ISS has performed 25 such maneuvers since 1999, according to the Natural History Museum. And researchers are developing ways to retrieve the waste in space, such as using hooks, nets and magnets to drag it back into Earth's atmosphere.