Based on a recent study published in The Astrophysical Journal , up to seven habitable planets could orbit a star under certain conditions. In our system, it would also seem that Jupiter played the spoilsport.

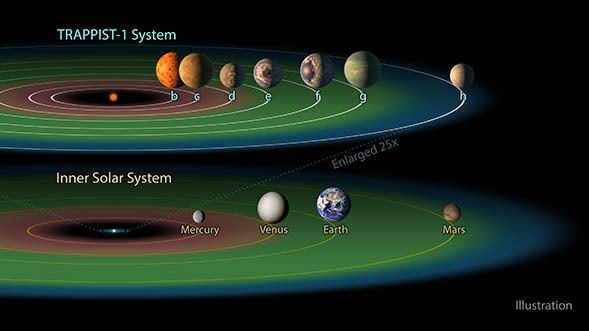

Discovered in 2017 39 light years from Earth, the TRAPPIST-1 system captured our imagination. And for good reason:imagine a star surrounded by seven planets, all rocky and similar in size to Earth. Among them,three evolve in the habitable zone of their star . Thus, one or more of these planets could, under certain conditions, harbor life.

The configuration of this system combined with the many rocky planets discovered around nearby stars in recent years has led astronomer Stephen Kane and his team at the University of California to Riverside, to ask the following question:how many habitable planets can a star have at most?

From our knowledge of planetary evolution, we know that you can't pack habitable worlds too close together. If this is the case, it would indeed disturb their respective orbits far too much. But where is the limit? As part of this work, the researchers performed some computer simulations.

Their conclusions are final. If you want to maintain both a minimum proximity between each world, but also ensure that a social distancing favorable to the development of life is respected, you can only pack up to seven habitable planets around one star .

According to the researcher, to have a habitable zone large enough to safely accommodate these seven worlds, a star should be 10 to 20% more massive than the Sun . Another requirement:these planets should travel in circular orbits , rather than in elliptical or irregular orbits. This in effect minimizes the "risk of interference" with other objects.

Finally, it would be better to have no Jupiter-like worlds around. According to the researcher, it is its presence that has limited the number of habitable planets in our system. Indeed, if we take the case of the Sun, which is a medium-sized star, this study suggests that it could at most shelter up to six habitable planets. That in itself isn't bad! However, and until proven otherwise, only one is today able to support it.

"Jupiter has had a great effect on the habitability of our Solar System, as it is massive (two and a half times the mass of all other planets in the System solar together) and disrupts other orbits “, he explains.

It now remains to identify the stars around which several "exoterres" could evolve. Leaving aside the TRAPPIST-1 system, the G-type star (similar to the Sun) Beta Canum Venaticorum (Beta CVn), which the researchers used as an example for their study, presents itself as a potential candidate.

To date, no exoplanets have been detected around this object, which in itself is not necessarily such a bad thing. Indeed, this suggests that no giant planet goes around it (if that were the case, we would have already identified it). By contrast, follow-up studies with next-generation instruments may eventually focus more on this star. They could thus isolate (or not) the presence of smaller worlds.

With their improved optics and sensitivity, these future observatories will also be able to collect spectra directly from the light reflected from the atmospheres of these planets. Armed with this information, astronomers can then isolate the presence of possible biosignatures.