Fifty planets have been confirmed by a new machine learning algorithm. Developed by researchers at the University of Warwick, this method could in the future maximize the number of discoveries.

To "hunt" exoplanets, telescopes rely on the transit method of detecting small and regular dips in stellar brightness. The latter can indeed testify to repeated passages of planets between the observer (the telescope) and the host star. However, this is not always the case. Indeed, these fluctuations can also be caused by the presence of a second star as part of a binary system. It may also just be the result of interference with an object in the background.

Once these elements are in hand, programs are then used to classify the potential candidates that the researchers must then analyze to confirm their presence or not. The problem is that telescopes nowadays collect an insane amount of data, so much so that it takes a lot of time to dissect it. However, that may soon change.

Researchers from the departments of physics and computer science at Warwick have indeed developed an algorithm based on machine learning, a form of artificial intelligence, to analyze a sample of planets potential. The goal is to unravel the real worlds from the "false positives".

To do this, the researchers trained their algorithm using two large samples of confirmed planets and false positives from the now-retired Kepler mission. They then used the algorithm on a dataset collected by the telescope that had not yet been studied in depth. Thanks to this method, they report having isolated about fifty confirmed planets.

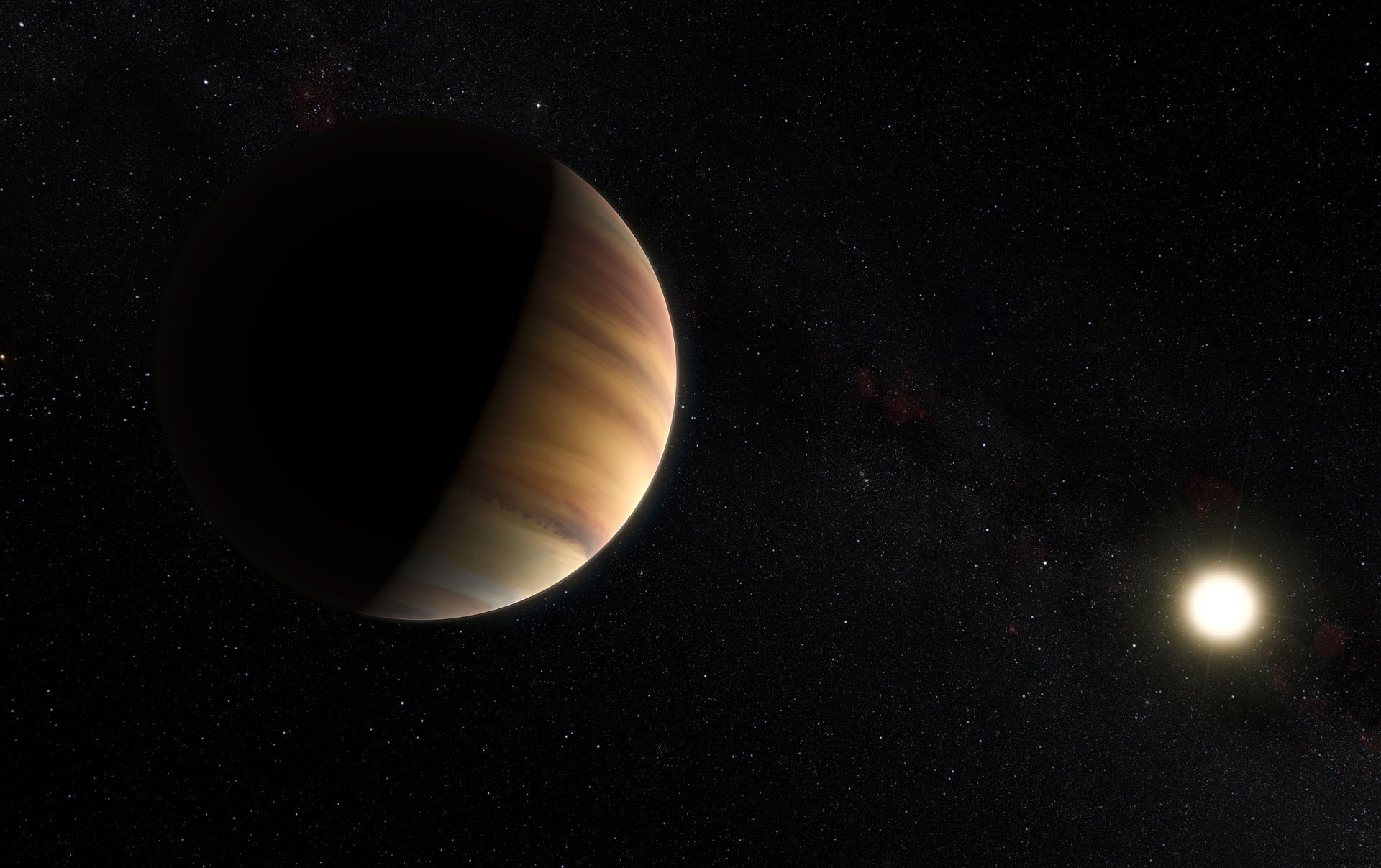

These planets are very varied. Some are as big as Neptune, while others are as small as Earth. Some go around their star in 200 days, while others, hot Jupiters, go around in just one day. Now confirmed, all these planets can be monitored by dedicated telescopes.

The researchers also aim to apply this same technique to other samples, such as those collected by the TESS mission, Kepler's successor. As a reminder, the satellite has just completed its two-year main mission and is now starting an mission extended for two more years .

“A survey like TESS should deliver tens of thousands of candidates over the next few years. And it would be ideal to be able to analyze them all in a coherent way "Said astronomer David Armstrong, lead author of the study."Fast, automated systems like this can lead us to validate these planets faster and more efficiently “.