An Australian telescope has scanned part of the sky for very low frequency extraterrestrial radio signals. But he came back empty-handed.

For several years, the SETI program has been working to search for traces of extraterrestrial civilizations in the Universe using radio telescopes. Last year, as part of the Breakthrough Listen initiative, astronomers relied on two large instruments – the Green Bank Observatory (USA) and the Parkes Observatory (Australia) – to detect possible radio signals at very low frequencies (techno-signatures) around 1,327 stars located less than 160 light-years away. Result:no extraterrestrial signs.

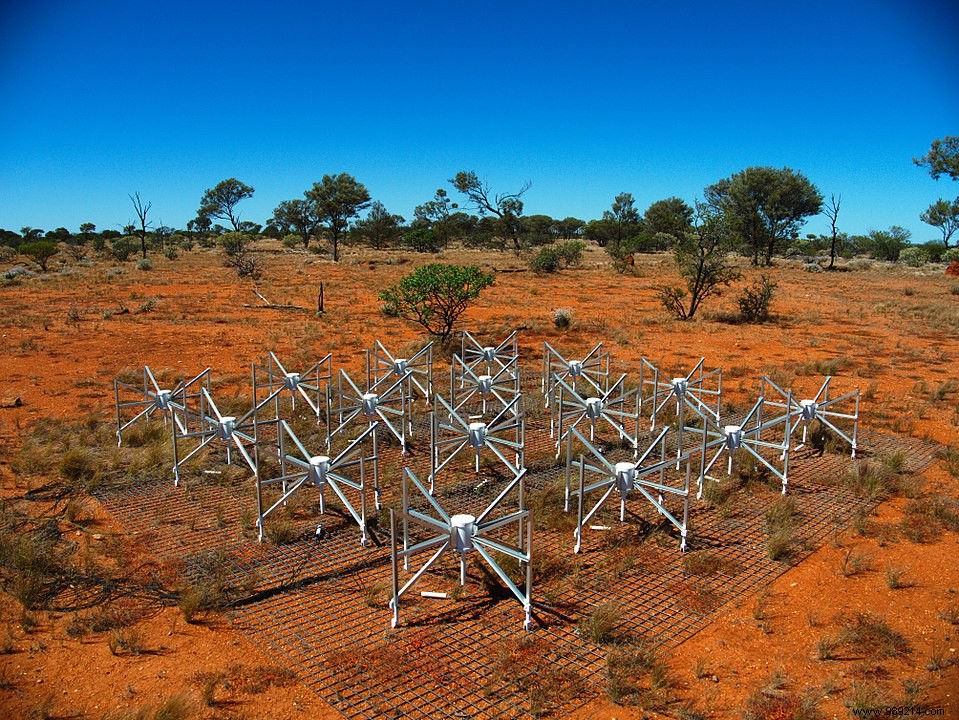

In a new investigation, SETI astronomers this time relied on the Murchison Widefield Array (MWA), in Australia. Thanks to this radio-telescope, they were able to probe the presence of these same techno-signatures around more than 10 million stellar sources of the Constellation of Veils. These contained six known exoplanets (there are likely many more in the region).

Unfortunately (or fortunately, depending), the results of this study revealed no signs of intelligent life in this region of the sky. At least not in the desired frequency range.

Astronomers Chenoa Tremblay and Steven Tingay (Curtin University), who initiated this investigation, nevertheless remain hopeful. Indeed, if this sample of 10 million stars may seem huge at first glance, it is actually only a tiny part of the Milky Way. As a reminder, our galaxy contains between 200 and 400 billion stars.

In addition, it is also possible that any signal emitted by an alien civilization is too far away. To take our example, we have deliberately only been generating radio waves since, at the earliest, the first radio transmission in 1895. This means that at best, our transmissions have only traveled about a hundred light years since then.

Furthermore, radio waves become less intense as distances get longer (inverse square law). At 100 light-years away, our radio waves are now probably indistinguishable from the cosmic background noise.

Finally, this type of study assumes that an advanced civilization has technology similar to ours. However, an intelligent life may not have developed the ability to communicate via radio signals.

Researchers intend in the future to rely on even more powerful telescopes – like the Square Kilometer Array (SKA). Its deployment is planned successively on two sites, in South Africa and then in Australia. Note that the Murchison Widefield Array is actually the first "block" of this future giant radio telescope.

A first commissioning (phase 1) is scheduled for 2024. Phase 2 will then be planned for the 2030s. Among other objectives, this telescope will be able to spot signs of possible extraterrestrial life in nearby solar systems.