A few days ago, the BepiColombo probe took advantage of a gravitational slingshot offered by Venus to gain speed and correct its trajectory leading it towards Mercury. The ship took the opportunity to take a nice picture of the planet.

Almost two years ago, the BepiColombo probe, the result of a collaboration between the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Japanese Space Agency (JAXA), was launched from Guyana with the aim of joining Mercury in 2025. Once there, the spacecraft is expected to release two orbiters, each landing in a different orbit. That of the ESA, the Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO), will carry out a complete mapping of the planet, while the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter (MMO) operated by JAXA, will aim to study its magnetic field and its magnetosphere. This mission should normally last one year.

However, reaching Mercury – the planet closest to the Sun – is no small feat. It is indeed a question of not starting in a straight line. To carry out its very energy-intensive journey, the BepiColombo probe must therefore rely on several planets in order to take advantage of their gravitational assistance. Nine of these maneuvers have been planned:one flyby of Earth, two of Venus and six of Mercury, before finally reaching its final orbit.

On April 10, BepiColombo performed its first flyby. During this maneuver, the probe approached to approximately 12,700 kilometers of the Earth's surface, positioning itself above the Atlantic.

On October 15, the spacecraft completed its first flyby of Venus, approaching to less than 10,720 kilometers of the planet, according to the European Space Agency (ESA).

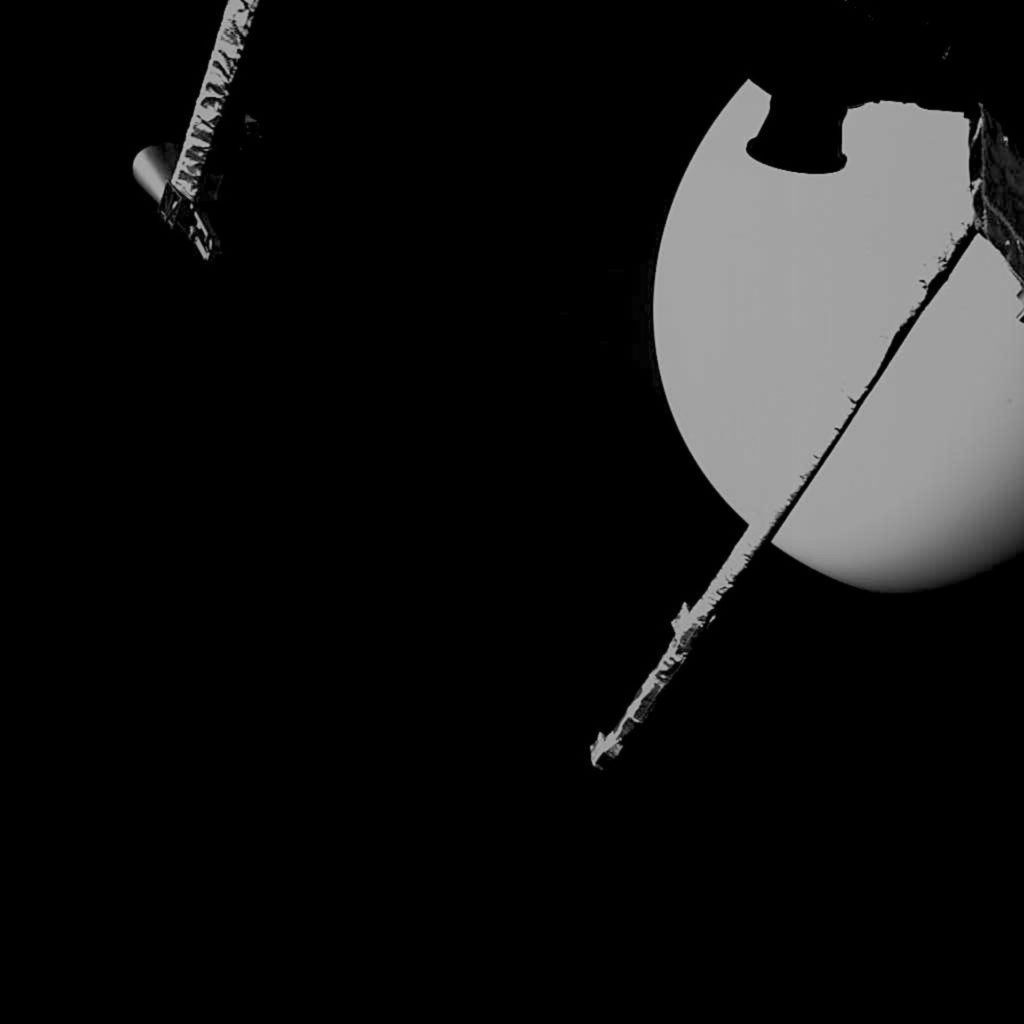

The mission engineers obviously took advantage of this new gravitational maneuver to photograph Venus. With the craft's main camera not yet available, the researchers relied on one of the probe's two small "selfie" cameras. In this image (below), Venus is about 17,000 km away . An antenna and a piece of the probe's magnetometer are also visible.

Other instruments active during the flyby allowed researchers to gather data on Venus' thick atmosphere, and the planet's interaction with the solar wind, the constant stream of charged particles flowing from the Sun through space. Other data will also be collected on the second flyby of Venus scheduled for August 2021.