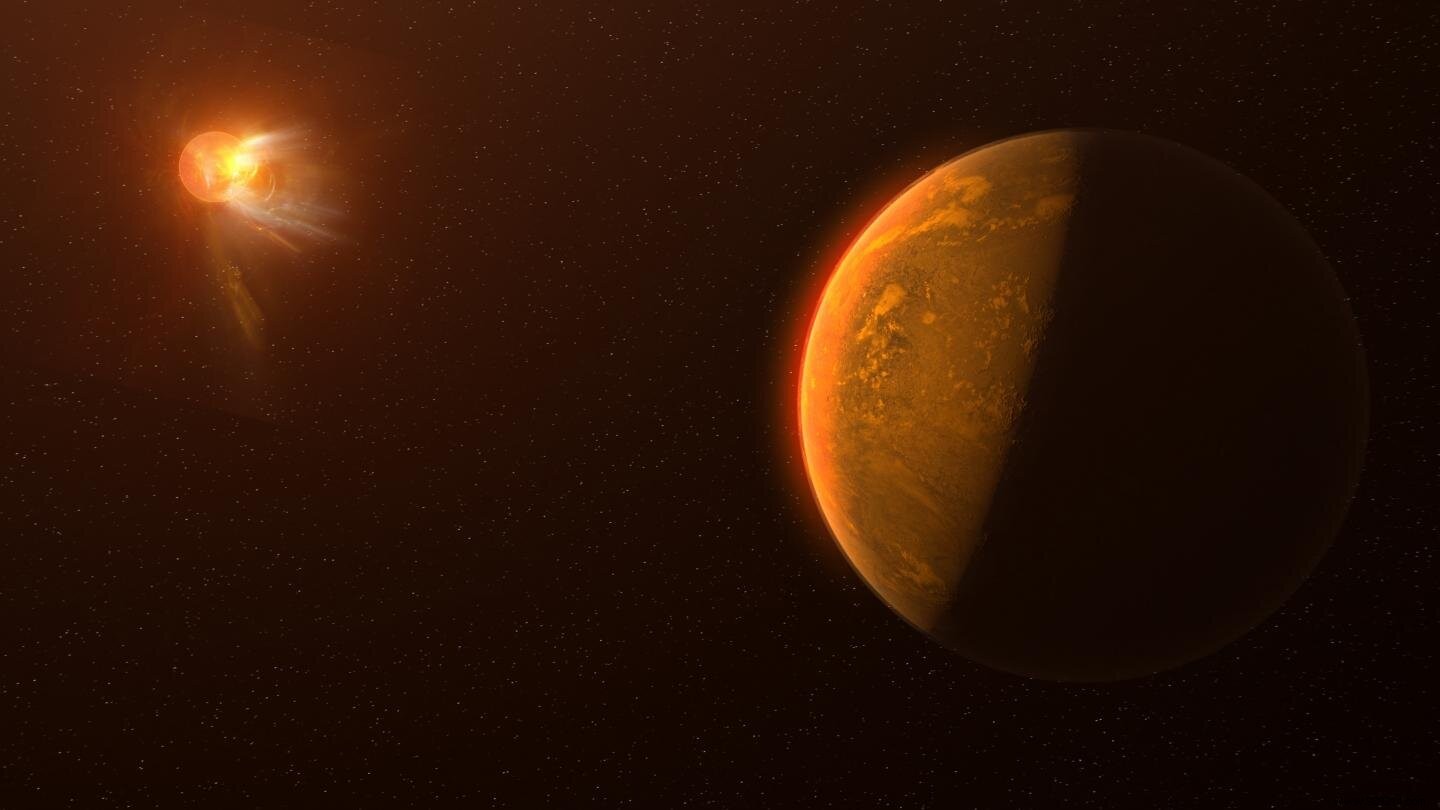

A few months ago, astrophysicists spotted the largest flare ever recorded on the star Proxima Centauri, the sun's closest stellar neighbor. Details of the study are published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Located just over four light years from Earth, Proxima Centauri is of interest to the scientific community for a very simple reason. Five years ago, a team from the European Southern Observatory announced the discovery of a terrestrial-like planet, since named Proxima Centauri b, evolving in the "habitable" zone of Proxima Centauri. Recent studies have highlighted the possible presence of a second planet around this star, but nothing confirmed yet.

Since the discovery of Proxima b, work has been carried out to determine whether or not this planet could harbor liquid water and, by extension, life. Nevertheless, it is worth paying attention to its star.

Proxima Centauri is a red dwarf eight times less massive and cooler than the Sun. This means that its habitable zone is closer to the stellar center. This is where the problems start. Indeed, if the red dwarfs are small compared to other stellar behemoths, they are on the other hand very active and unstable, regularly projecting stellar eruptions in their surroundings . And Proxima Centauri is no exception to the rule.

In a recent study, University of Colorado researchers led by Meredith MacGregor relied on nine instruments to observe the star in 2019. Among them These included the "eyes" of Hubble, the Atacama Large Millimeter Array (ALMA), and the exoplanet hunter TESS. During forty hours of observation (spread over several months), five of these instruments recorded an incredibly powerful "flare" (burst of radiation). "The star has become 14,000 times brighter into ultraviolet wavelengths within seconds “, according to Meredith MacGregor.

To put this into perspective, the event was about a hundred times more powerful than any other similar eruption observed on the surface of the Sun.

Observed on May 1, 2019, the event lasted only seven seconds. Although it didn't produce much visible light, it did generate a huge burst of ultraviolet and radio radiation . "So this is the first time we've been looking for millimeter flares “, emphasizes the astrophysicist. These millimeter signals could help researchers gather more information about how stars generate flares.

Note that this type of thrust is not uncommon on Proxima Centauri. In addition to this event wiped out on May 1, 2019, the researchers recorded many other flares during these forty hours of observations. For the planet or planets evolving around this star, these events would be almost daily. Over time, such energy could then strip their atmosphere, exposing the life forms evolving below to deadly radiation .

"If there was life on the planet closest to Proxima Centauri, Proxima b, it would have to be vastly different from anything on Earth “, concludes the astrophysicist. "Otherwise she just had a really bad time" .

In 2017, a team of astronomers had already detected a gigantic stellar flare on the surface of the star. This eruption had been so powerful that "earth-type" life would have had no chance of surviving .