Voyager 1 instruments recently detected the faint and constant "humming" of plasma in interstellar space. It's a first. This work, signed by researchers at Cornell University, was published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

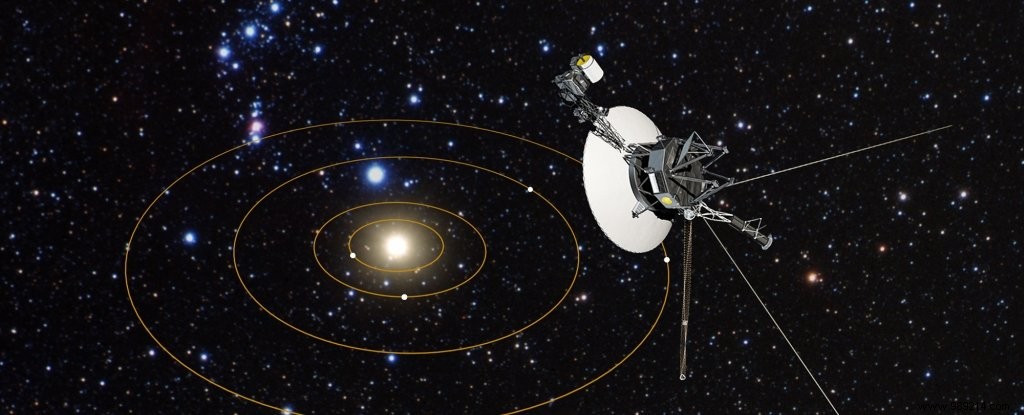

In interstellar space, far from the Kuiper belt, the American probe Voyager 1 has been continuing its journey for nearly forty-five years. The ship is now moving more than twenty-two billion kilometers from our planet. And yet, we can still communicate with him.

By examining the data slowly returned by the probe, Stella Koch Ocker, a doctoral student in astronomy at Cornell University, isolated a constant and persistent emission produced by the thin near-vacuum of interstellar space between two disturbances caused by solar flares. "This is a very low, monotonous hum, as it occurs in a narrow frequency bandwidth “, specifies the astronomer.

This hum (3 kHz) is that of plasma, matter so hot that electrons have been torn from their atoms. The detection of this plasma alone is insignificant. After all, it is one of the most abundant forms of visible matter in the universe. Importantly, however, the probe had so far only detected strong disturbances in the plasma (oscillation events) triggered by coronal mass ejections from the Sun.

Here Voyager 1 has recorded natural background plasma levels , or ambient, which are not influenced by our star.

Concretely, imagine the interstellar medium as a calm rain. In this environment, a solar explosion sometimes manages to slip as far from our star, acting like a thunderbolt in a thunderstorm. Then the rain comes again. Voyager 1 has just detected the "sound" of this light rain.

This new work allows researchers to better understand how the interstellar medium interacts with the solar wind, and how the protective bubble of the heliosphere is shaped and modified by the interstellar environment.

Shami Chatterjee, co-author of this work, emphasizes how important the continuous monitoring of the density of interstellar space is. “We never had a chance to review it. Now we know that we don't need a fortuitous event related to the sun to measure interstellar plasma “, notes the astronomer. Thanks to Voyager 1, researchers will be able to follow the spatial distribution of plasma, even when it is not disturbed by solar flares.

This new detection is therefore very important for researchers, but remember that Voyager 1 and its twin Voyager 2 were not specially equipped to analyze this environment. The main objective of this program was indeed to collect scientific data on the outer planets of our system.

That's why a NASA team is currently working on the development of a new mission to probe this environment. The proposed probe would aim to collect data up to 1,000 AU from the Sun.