Roscosmos, the Russian federal space agency, is working on the development of a mission to explore Jupiter. During this journey, which is expected to last approximately fifty months, the nuclear-powered vessel will make two "pit stops".

So far, only NASA has reached Jupiter. The first exploration of the planet and its satellites dates back to 1973, with the flyby of Pioneer 10. In 2016, a dozen space missions also quickly visited the patron of the solar system, mainly to benefit from its gravitational assistance with the aim of reach another destination. Only two of them, Galileo and Juno (recently extended), have conducted extended missions there.

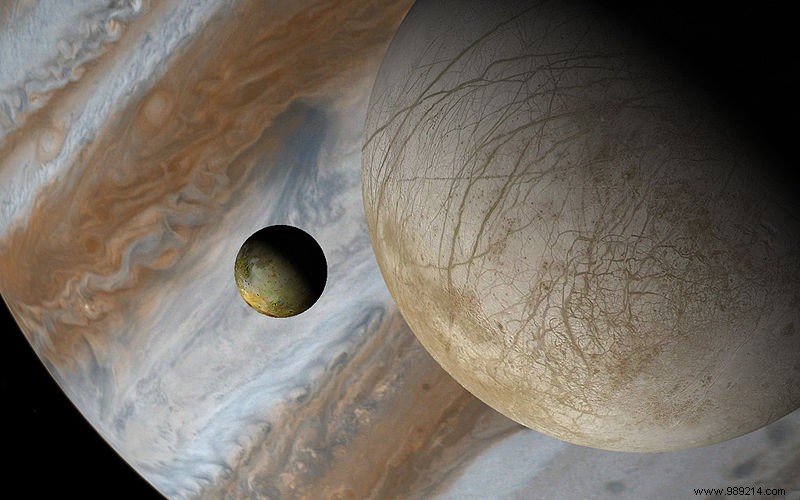

Next, the European Space Agency is developing its Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE) mission, scheduled for launch in 2022. This will be the first mission to the outer planets of the solar system which will not be proposed by NASA. The probe will make repeated flybys of the moons Callisto, Europa and Ganymede. It will then place itself in orbit around the latter from 2032 for a more in-depth study.

Finally, three years ago, NASA confirmed its intention to focus on Europa. We know that the moon shelters under its surface a global ocean, a priori salty, capable of supporting life. To try to determine it, the American agency is preparing a mission called Europa Clipper. The probe was normally scheduled to be launched in 2024 aboard a private launcher, with an expected arrival in 2029 or 2030.

That being said, it would seem that Russia also has its sights set on the Jovian system. Roscomos, the country's space agency, has just announced a plan to explore Jupiter.

During its journey, which is expected to last just over four years, the probe will make a first "pit stop" around the Moon to drop off an orbiter. Next, the craft will pass by Venus to perform a gravity assist maneuver. Russia will also take the opportunity to deliver an exploration probe on site, before venturing to Jupiter.

Most spacecraft rely on solar panels to convert solar energy into electricity. However, the deeper a spacecraft goes into space, the less solar energy is available. As part of this mission, Russia will use a complete 500 kilowatt nuclear reactor dubbed Zeus, relying on fission reactions to drive propulsion.

Some missions – such as Cassini and Voyager – were powered (and still are for Voyager probes) by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), which is a much like a nuclear battery using heat from the radioactive decay of isotopes. However, RTGs are not nuclear reactors per se, as there is no chain reaction.