A study suggests that the most extreme space weather events, like solar storms, are more predictable than previously thought. The second half of this new decade, during which the United States aims to set foot on the Moon, could also be particularly at risk, warn researchers.

In 2017, the Trump administration asked NASA to return humans to the Moon as early as 2024. The objective of this program, named Artemis, will be to establish facilities permanently inhabited in the south pole region. We knew from the start that the 2024 deadline was perhaps a bit ambitious. On the other hand, we know that the US House of Representatives would seek to push this landing mission to 2028, consistent with previous NASA goals.

A priori, the return of humans to the Moon should therefore take place between these two deadlines. But is it really wise? New research indeed suggests that the Sun may have a say.

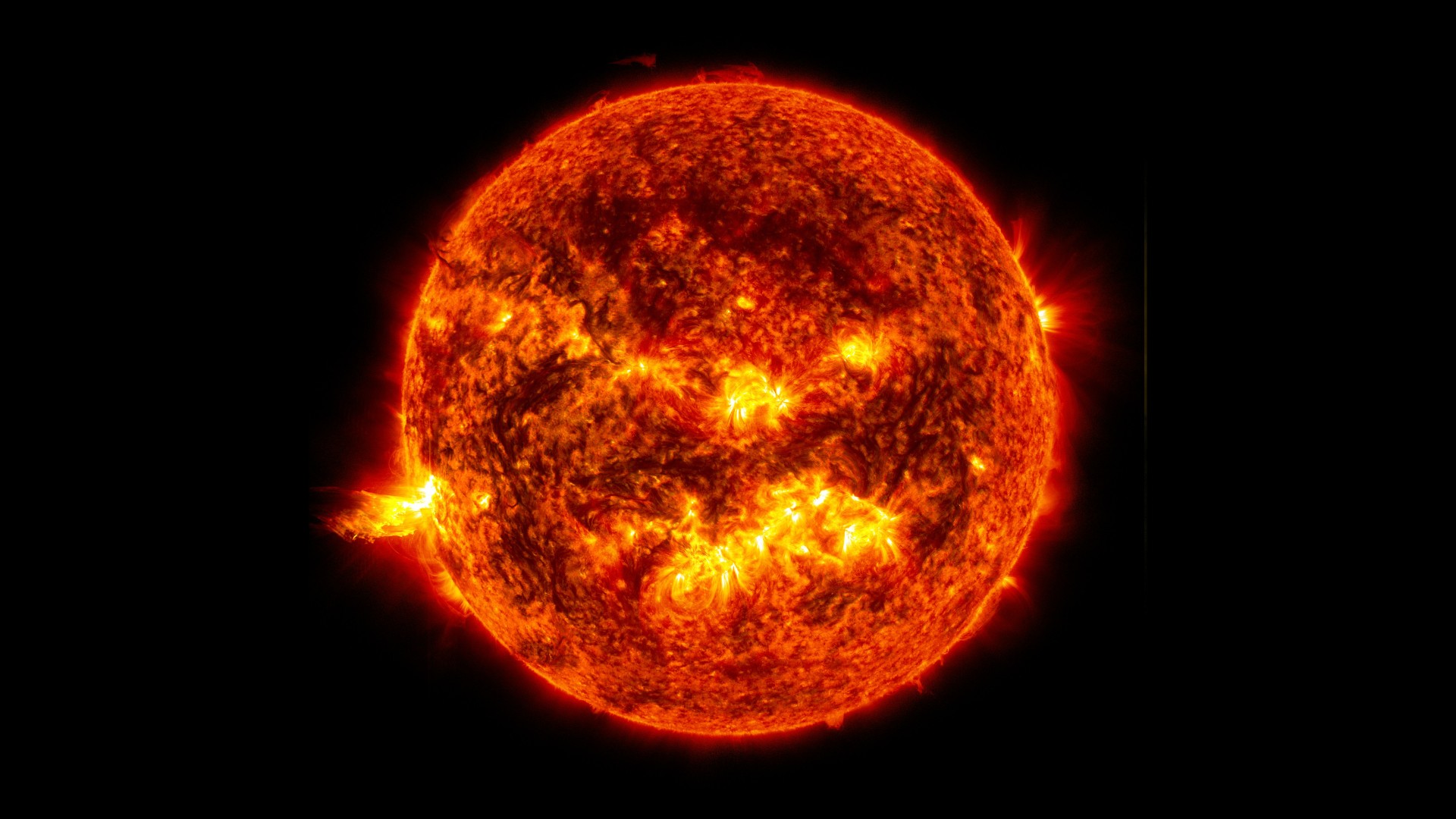

The solar cycle of the Sun's magnetic field lasts about eleven years . The solar minimum is the part of the cycle that offers the least activity. The solar maximum, driven by the reversal of the magnetic poles of our star, is therefore the most active. It is usually around this time that major solar flares occur.

That being said, we are currently at the start of cycle 25 . And the start of the next solar maximum is predicted for July 2025. As part of a new study published in the journal Solar Physics , researchers have determined that during even cycles, solar storms are more likely to occur early in the cycle. Conversely, during odd cycles, they tend to develop towards the maximum end.

Since cycle 25 is an odd cycle, we should expect more solar storms in the second half of this decade. We know that solar storms can pose a risk to satellites, spacecraft and astronauts. Also, sending humans to the Moon during this time, away from Earth's protective field, could add additional risk to already high-risk missions.

“Until now, the most extreme space weather events were thought to be random in their timing and therefore there was not much we could do to plan around them. of them ” , underlines Mathew Owens, spatial physicist at the University of Reading. “ However, this research suggests that they are more predictable, generally following the same “seasons” of activity as smaller space weather events ” .

With this pattern in mind, the researchers note that any major space mission planned between 2025 and 2030 should take into account this higher risk of extreme space weather, and plan responses accordingly.