Venus may still be geologically active. In a recent study, supported by observations made by the Magellan mission, researchers have identified several pieces of crust visibly deformed in the recent past. This work could allow us to learn more about the early Earth.

Long held in the background behind Mars, Venus will once again come back to center stage. A few weeks ago, NASA announced the selection of the DAVINCI+ and VERITAS missions – both finalists of the Discovery program – whose launches are scheduled for the end of the decade. More recently, the European Space Agency (ESA) also confirmed the development of its EnVision mission during the same period.

These three projects will aim to solve a real planetary enigma. Earth and Venus are the same size, are relatively close together, and are made of the same stellar material. Yet these two worlds have taken two different paths. On one side the Earth is an oasis, on the other Venus is an acid-strewn hell. The question is:why?

A recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences could give us some answers.

We know that the face of our planet has constantly evolved since its formation at the rate of the movement of tectonic plates, like gigantic pieces of a geological puzzle. Venus has no plate tectonics. On the other hand, she could have developed a slightly strange variant of this process.

Specifically, a team of researchers found that the Venusian surface was at least partly made up of pieces of planetary crust that are likely to collide with each other even today , like huge pieces of ice floe could do it over rough seas.

This type of activity, which does not constitute true plate tectonics, would involve nearly sixty pieces of crust called campi – "fields" in Latin – and their size varies from Ireland size to Alaska size, according to the Times .

“We have identified a previously unrecognized pattern of tectonic deformation on Venus that is driven by inward motion just like on Earth” says Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at North Carolina State University. “While different from the tectonics we currently see on Earth, this is still evidence of inner movement expressed on the surface of the planet” .

This new discovery is significant, as the interior heat driving this Venusian geologic activity appears similar to that developed on Earth about 2.5 to 4 billion years, stresses New Scientist . If this is indeed the case, this "modern" Venus could allow us to learn more about the primitive version of the Earth.

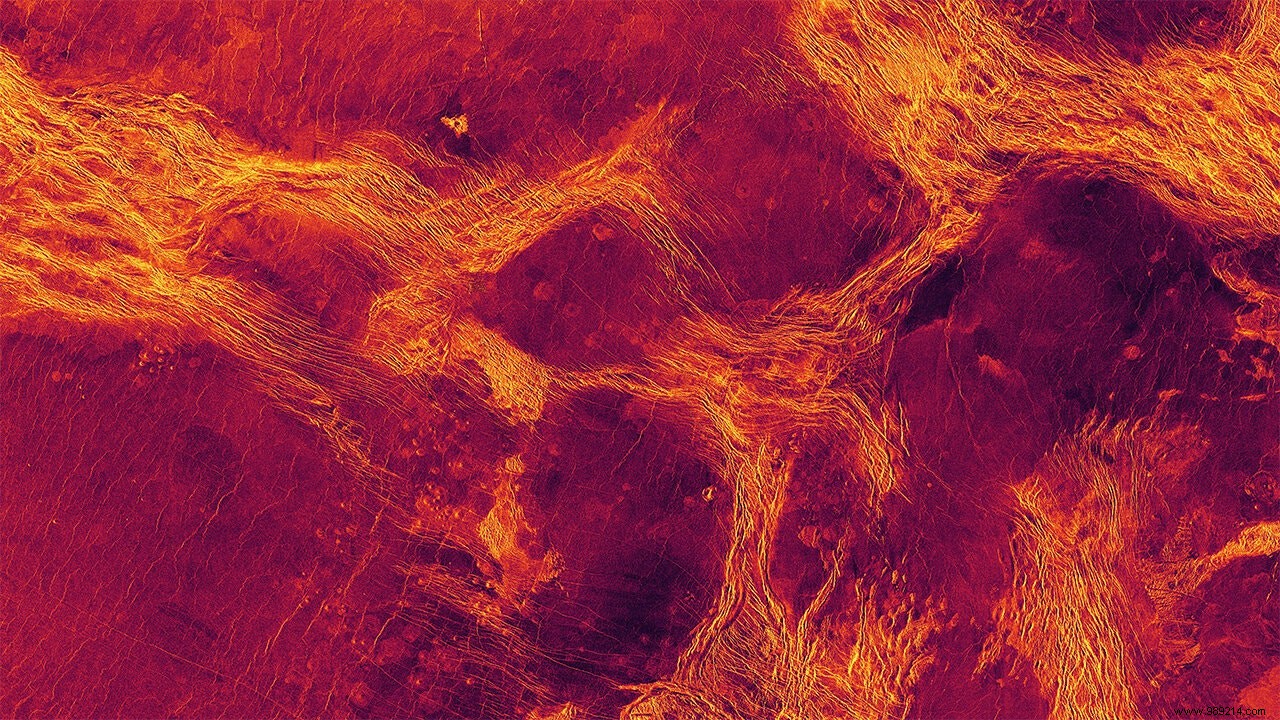

The results of this work are based on a reanalysis of radar images of the surface of Venus captured by NASA's Magellan mission, which ended operations in 2004. At the At the time, the probe deployed radar to scan the planet's atmosphere and map its surface. On these images the researchers then identified the famous "campi" mentioned above.

The team then integrated these observations and measurements of Venus' gravity field into a computer model to generate geological scenarios that might produce what they observed. This work suggests that the movement of the planet's fluid mantle does indeed result in deformation of its surface on Venus.

Whether this process is still ongoing today remains to be seen. It is to this question (but not only) that the future missions under development will have to answer. If so, then Venus would still be geologically active.

Explaining this strange "tectonic tempo" might also be helpful in exoplanetary research. There are indeed in our galaxy billions of worlds similar to ours or to Venus whose evolution can be guided by the presence or not of plate tectonics.