Researchers suggest that the possible bodies of liquid water isolated under the surface of Mars a few months ago are actually layers of clay. Divided into several studies, this work has been published in the Geophysical Research Letters.

Three years ago a team of researchers surprised the scientific community by assuming the presence of a body of liquid water buried under the icy surface of the Martian south pole. This body of water about twenty kilometers wide and not very deep "looks like one of the interconnected basins located under several kilometers of ice in Greenland and Antarctica “, detailed at the time Martin Siegert, of Imperial College London. Last year, these same researchers also described the discovery of possible new water bodies in the same area.

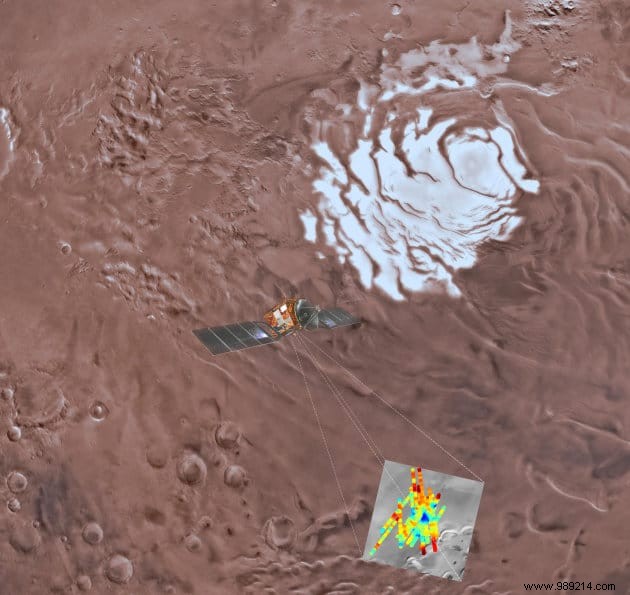

For these studies, the researchers relied on data from a radar installed on the Mars Express (ESA) probe called MARSIS. Radar signals, which can penetrate rock and ice, change when reflected from different materials. In this case, they would have produced particularly bright signals at approximately 1.5 km below the surface, suggesting that they could not have passed through liquid water.

If validated, this new discovery could truly be a game-changer in the field of exobiology. Indeed, similar subglacial lakes are known to harbor microbial life on our planet. However, a re-examination of the collected data combined with laboratory analyzes suggests another explanation for the recorded signals.

Shortly after the study was published in 2018, several dozen researchers gathered for the International Conference on Mars Polar Science and Exploration in Ushuaia. These meetings provide an opportunity to discuss the latest findings and test new theories. Naturally, many discussions revolved around these famous underground lakes. Several scientists then began to think of ways to test the underground lake hypothesis.

A team from Arizona State University focused in particular on the analysis of 44,000 radar echoes recorded over fifteen years by the MARSIS instrument at the Martian south pole. The researchers found several dozen "bright highlights" like those in the 2018 study. In contrast, many of these signals were isolated to areas near the surface. However, it is too cold for the water to remain in a liquid state , even if you mix it with perchlorates, a brine commonly found on Mars that helps lower the freezing temperature of water.

Two other teams then analyzed these signals to determine if any material other than liquid water could produce them. Very soon, all eyes turned to a group of clays called smectites formed by liquid water on Mars long ago.

The researchers then tested their hypothesis in the laboratory. To do this, they placed samples of smectite frozen at minus 50°C in a cylinder designed to measure how radar signals would interact with them. As a result, the response of these materials corresponded almost perfectly to the 2018 radar observations . Based on data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO), the researchers then confirmed the presence of these clays near the site of the radar observations.

These new articles therefore offer a more plausible explanation for the observations recorded. Naturally, the only way to be sure would be to get there and dig deep under the ice. But for now, it's impossible.