As strange as it may seem, Japanese researchers plan to launch a first wooden telecommunications satellite as early as 2023. That said, their project still has many areas of concern. 'shadows.

A few weeks ago, researchers at Kyoto University, in partnership with the Japanese company Sumitomo Forestry, announced their intention to build – and then release into the space – a wooden satellite, reads a BBC article. While wood does have many qualities as a building material, this idea of a "WoodSat" has since been widely criticized.

First, because many have imagined this approach as a response to the growing problem of space debris in low Earth orbit.

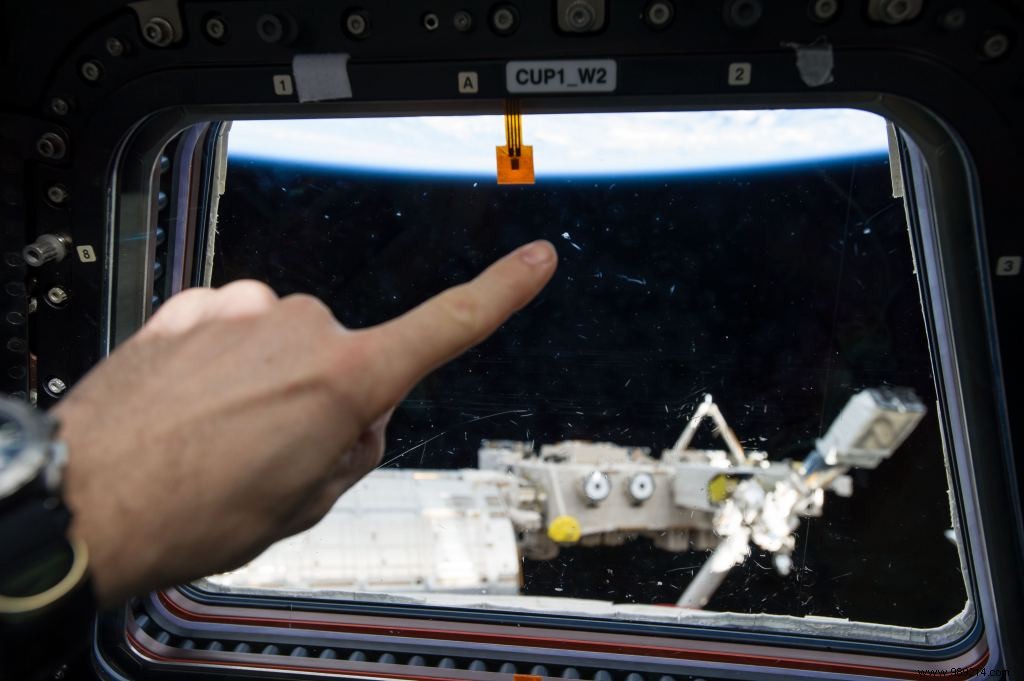

There are currently more than 34,000 pieces of man-made space debris larger than ten centimeters in orbit around the Earth. These objects, which spin through space at over 7.8 kilometers per second , pose a real threat to active satellites and other occupants of the ISS. In 2019 alone, the International Space Station had to use its thrusters to dodge a piece of debris three times.

That being said, the fact is that these objects or debris, whether metal, plastic or wood, will always spin at the same speed and will always represent a danger potential.

How about addressing the question of the atmospheric re-entry of satellites? The idea of proposing wooden objects capable of disintegrating more easily than traditional debris may seem more interesting than simply trying to respond to the growing problem of space debris in Earth orbit. After all, satellites incorporate many exotic – sometimes toxic – compounds that can further pollute our planet.

Unfortunately, again, making a wooden frame might not make much of a difference, as the electronics inside will still need to be made conductive compounds.

A possible advantage to these possible "Woodsat" would be that wood is a material largely "transparent" to radio waves, which means that builders could maintain most antennas of communication and research within their framework. In other words, we would not necessarily need to deploy these often very cumbersome instruments after reaching orbit. Especially since these "deployment failures" have already got the better of many satellites. Here it would no longer be a problem.

We also don't yet know what type of wood will be preferred. The latter, exposed to strong temperature fluctuations once in space, will nevertheless have to present a low thermal expansion .

That's about all we know for now, except that Japanese researchers plan to come up with several designs in the coming months, before to operate a first launch in 2023 . In the meantime, other details may be provided.